Actors in Masks, 2020

The first time I can recall seeing the iconic Comedy and Tragedy masks, known as Thalia and Melpomene, I was in the fifth grade looking at the cover art of a program for my big sister’s show at Sutton High School. I remember being quietly enamored with their over-exaggerated smile and frown. Shortly thereafter, I found myself identifying very strongly with teenage thespian culture. For me, that manifested itself in a deep love of Claire Danes’ work in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo and Juliet and a notebook hand decorated in the very symbol of theatre itself, masks.

THE PAST

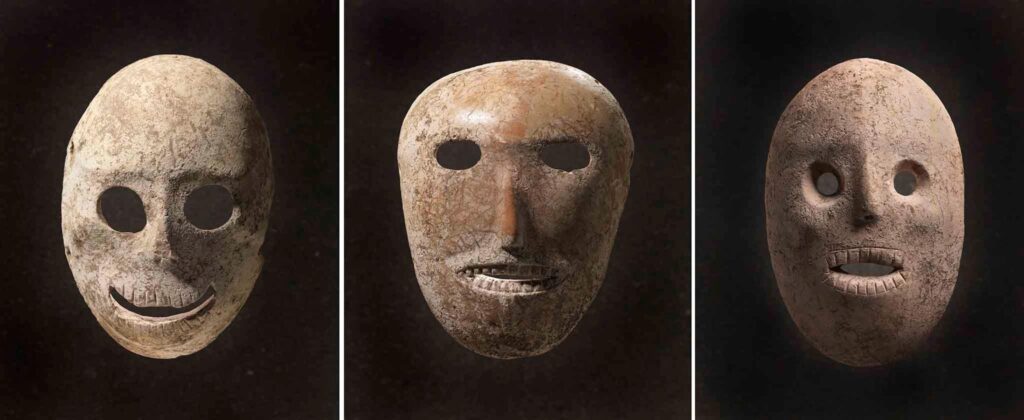

The history of masks in our world is vast and dates back more than 9,000 years. Masks have been worn for tribal ceremonies, religious rituals and theatrical productions, with strong roots in many places including, but not limited to, ancient Egypt, Africa, Japan, Greece, Rome, Latin America, Southeast Asia and North America (Wilson). By contrast, the documented history of masks worn by the health community that resembles today’s usage spans less than 200 years (Strasser).

THE PRESENT

We are living through a pandemic. Each day we are reminded by our leaders, by store fronts, advertisements and social media channels to “wear a mask.” In April they were scarce. Now, nearly every designer in the world has their own line of masks. You can find masks at your local grocery store, gas station and, of course, hanging off the rear-view mirror of every car you pass on I-290. Thus, this September when I read through one of Troy Siebels’ earliest adaptation of A Christmas Carol Reimagined, it was extremely resonant to read the stage direction, “Marley’s Ghost enters, wearing a mask (theatrical, not covid).” I found myself transported to college acting classes where I first studied and wore Italian-inspired commedia dell’arte masks. I remembered a time not so long ago when wearing a mask meant transforming oneself, looking in the mirror and creating an identity and a physicality outside the recognition of the wearer. I read these stage directions and longed for that day when I could safely share a space with an actor wearing a mask “theatrical, not covid.”

Last month, I was gifted the experience to work on A Christmas Carol Reimagined. We wore surgical masks every day at rehearsal in addition to taking three COVID-19 tests weekly, along with many other safety precautions required by Actors’ Equity Association. Our cast was slimmed down from 30 to just eight actors. For the audience to travel on this journey with us, each actor had to be completely immersed in the storytelling, bearing more weight on their shoulders than ever before. It’s not difficult to understand why transforming the actors with theatrical masks was important to our director, Troy Siebels. And if you haven’t guessed, masks were my favorite addition to this year’s production.

I reached out this week to our costume designer, Gail Astrid Buckley, to learn more about how the masks used in ACCR were selected.

“An important clarification I got from Troy regarding his vision for using theatrical masks in the costume design: It wasn’t just to differentiate the actor, but to add a ‘ghostly’ appearance or aspect to the spirits. It made them appear quite different to the other characters.”

There are four theatrical masks used in our production, each very different, but also cohesive. The Ghost of Jacob Marley, Christmas Past and Christmas Present wear half masks, which leave their mouths exposed. Alternately, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come wears a full faced mask, and I personally found the final look to be reminiscent of Studio Ghibli’s “No Face” from Spirited Away.

“I was able to purchase blank masks that had a specific look to them that was close to what we were looking for in the characters, slightly creepy, but still interesting. I painted and embellished them to add to their characters” (Buckley).

A fascinating wrinkle in our process: The first week rehearsing in these Buckley-embellished masks involved a surgical mask layered under the theatrical mask. I found this initially a bit challenging to navigate as an associate director, but it made our final weekend with the actors especially thrilling. Witnessing the fully realized creation of each Spirit felt sacred.

After weeks of rehearsing without seeing anyone’s mouths or noses, the removal of surgical masks for our weekend of filming was an incredibly unique experience for all the actors. For me personally, feeling my own face “naked” was a slight distraction. I had grown quite comfortable behind my surgical mask. However, the gift of seeing facial expressions outside of my own household, live and in person, not on a Zoom meeting, not facetiming on my phone, was a gift I received with open arms (albeit socially distanced from six feet apart).

THE FUTURE

I’m looking forward to the time when wearing a mask is reclaimed by artists. I’m looking forward to the time when the first mask that comes to mind is one that transforms the wearer and transports the spectator. I’m looking forward to meeting a fifth-grader who sees those iconic comedy and tragedy masks and is inspired to imagine and explore the meaningful world of play behind them.

Sources and Further Research:

Ancient Greek Masks. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyQFtJfOonI

Behind the Mask of the World’s Oldest Surviving Dramatic Art | Short Film Showcase. Directed by Edwin Lee. National Geographic Youtube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gsa2GpIWKKQ

Buckley, Gail Astrid. “Quote/Commentary Re-ACCR Masks.” Received by Annie Kerins, 1 Dec. 2020

Strasser, Bruno J. and Thomas Schlick. “A history of the medical mask and the rise of medical masks and throwaway culture.” The Art of Medicine Lancet . Volume 396, Issue 10243. 4 July 2020, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31207-1/fulltext 1 Dec. 2020.

Williams, A.R. World’s Oldest Masks Modeled on Early Farmers Ancestors. National Geographic. 10 June 2014, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/6/140610-oldest-masks-israel-museum-exhibit-archaeology-science/ 3 Dec. 2020.

Wilson, Edwin, and Alvin Goldfarb. Living Theatre: a History. McGraw Hill Company, 2004.