Q&A with Anaïs Mitchell (writer & composer of Hadestown) and Rachel Chavkin (director of Hadestown)

Question: What inspired Hadestown?

Anaïs Mitchell: I was just at the beginning of a career as a singer-songwriter and I was driving from one tip gig to another when the melody of “Wait for Me” dropped out of the sky. It came with some long-lost lyrics that seemed to describe the Orpheus & Eurydice myth, which had been a favorite of mine as a kid. I started to follow the thread into the labyrinth and I think what inspired me most about retelling that story was the idea of pitting young, creative, optimistic Orpheus against an underworld where “the rules are the rules.” Over many years of development, I’ve identified with many different characters. But at first it was the idea of Orpheus, who believes if he could just write something beautiful enough, he could move the heart of stone, he could change the way the world is—that was inspiring to me.

Question: Rachel, was there something specific that drew you to Hadestown?

Rachel Chavkin: I’ve never encountered a score that feels so singular in its style while still taking up some of the storytelling rules that musical theater goes by. Hadestown is by far the hardest thing I’ve ever directed. It was a delicate balance as to how much to keep it feeling like a concert versus a play.

Question: Anais, you and Rachel seem to be the winning combination. How did you meet, and what has the collaboration been like?

Anaïs Mitchell: In 2012 I saw the Ars Nova production of Dave Malloy’s Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812. I was completely awestruck and I thought, “Who’s that director?” It turned out to be Rachel. Hadestown began as a DIY community theater project in Vermont, then became a studio album and a touring concert, and at the time I met Rachel I was searching for a way to develop the piece into a full-length professional musical. Great Comet, like many of Rachel’s shows, had this combination of highly accessible Broadway-style entertainment, and also real unapologetic downtown weirdness. Rachel has a great feel for music and musicals and how to bring the best aspects of concert culture into the theater. But what turned out to be the most essential thing about my collaboration with her is that Rachel’s a gifted dramaturg, and she’s not afraid to really roll up her sleeves in the development process of a show. We worked together for three years before we got an off-Broadway production, and three more before we landed on Broadway. She pushed me—a songwriter with almost no dramatic writing experience—to write, and rewrite until the drama was satisfying.

Question: There are a lot of women that brought Hadestown to life. From Anaïs’s writing to Rachel’s direction, and Rachel Hauck’s scenic design. Was this intentional?

Anaïs Mitchell: You know, I had no idea Rachel was a woman when I fell in love with her work. I don’t think it was our intention to build a female-led team, but we sought out the folks whose work we responded to most, and many of them were women. A big part of the equation is that our two lead producers are women: Mara Isaacs and Dale Franzen. I will say it was an extraordinarily empowering experience working with so many women. I felt my instincts were really trusted. Challenged at times, of course! But ultimately, trusted in a deep way.

Question: When casting and building the show, Rachel and Hadestown’s production team were extremely mindful of diversity and inclusion. Anaïs, did you write Hadestown with particular people in mind?

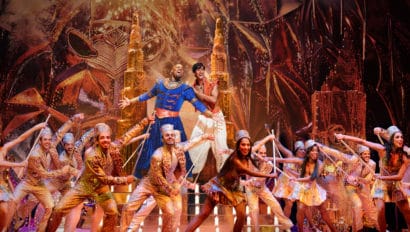

Anaïs Mitchell: All of Rachel’s shows are gloriously diverse. Theater depicts and celebrates humanity, and humanity is diverse. The main thing we were looking for in our casting was a kind of singular rockstar unicorn quality. The music is really built for people to bring the individual force of their personality to it.

Question: Rachel, did you intend to build a diverse cast?

Rachel Chavkin: Oh, absolutely! I think diversity is inextricable from excellence, and I think all too often people, and in particular the dominant culture tends to frame it as a choice that you have to make between diversity and excellence. I personally think it’s the opposite. I think a [diverse] room is far more interesting, just purely on a dramatic level. It’s so much better stylistically, emotionally to have varied voices. And so yes, with Hadestown specifically, we have reaffirmed time and again that racial diversity in particular is core to our vision of excellence.

Question: When Hadestown moved to Broadway, the show sought out theater critics of color to review it. Was it important to you to get a wide variety of critiques of the show?

Anaïs Mitchell: We desperately need a diversity of voices in our criticism. How else will criticism be able to speak to people in a meaningful way?

Question: Rachel, can you tell me why creating spaces for diversity and inclusion in your projects is so important to you?

Rachel Chavkin: I think specifically because I am a white woman in the sense that I am part of half the world’s population that can live our lives every day with the knowledge that we are vulnerable to the other half of the world’s population. I have felt gender as a determinant in my career path multiple times and in multiple ways. I have experienced sexual harassment and sexual assault and so I am on that side of the equation of when it comes to that. And at the same time, I have enormous privilege that comes with whiteness, that also comes with having two highly educated parents who made me the center of their [world]. I grew up enormously fortunate in terms of my family’s ability to invest in me and my interests. To quote a franchise, with great power comes great responsibility. I had the ability.

Question: The show has traveled a lot pre-Broadway. How have the out-of-state audiences influenced the editing of the show?

Anaïs Mitchell: Hadestown had a very long road to Broadway, with pitstops not just out of state but out of country. We did a production in Edmonton (Canada) in 2017 and then London’s National Theatre in 2018. The Edmonton production was so important, as we were trying to figure out how to “scale-up” the show from the tiny, in-the-round version at New York Theater Workshop, to a proscenium-style theater, with a larger ensemble of actors. We learned so much from those Canadian audiences about what the show did—and didn’t—want to be. It was powerful to perform the show in London on the Olivier Stage that has presented so many classic Greek works and Shakespeare plays. I remember Rufus Norris, the director of the National Theatre, expressing views that often put art before commerce—for example, he was not a great fan of “buttons” (those zazzy definitive endings of songs that encourage the audience to applaud, which appear SO often on Broadway). And it felt timely to be telling this tale in the UK in the thick of Brexit. It’s incredible the way there are regional differences in terms of which lines people find funny, which scenes they find tragic, which songs make them dance in their chairs.

Rachel Chavkin: You know, I tend to try to trust the fact that the audiences are really smart and also they are very individual. An audience in Texas is going to experience a very different thing than an audience in California than an audience in Minnesota. And so all I can really do as a director is try to adjust to what feels most meaningful to me. And then I have to trust that because I’m not an alien. Some other humans out there will resonate with it as well.

We did, however, do the show off-Broadway, and then took it to Canada, and did it for the first time in proscenium and I made a number of mistakes when we first brought it into proscenium for a larger audience. I let the production get to what in the theater we call representative. I literalized the metaphor and me and my set designer, Rachel Hauck, we actually put railroad tracks on stage. Because there’s the lyric, “On the road to hell, there is a railroad line…” And that turns out it’s a really bad idea to try to stage a metaphor. I can laugh about it now.

Question: While Hadestown is loosely based on characters many fans of Greek mythology may know, who was the hardest character to write for and why?

Anaïs Mitchell: Orpheus was by far the hardest character for me to write, in part because he’s more “pure” than any other character. Hades, Persephone, and even Hermes and Eurydice have a sort of jaded quality, a world-weariness that is much easier to grasp and to write for. Orpheus is a dreamer, a genuine optimist, and that has been a challenge to discover and to express in writing. It’s hard to take an optimist seriously! For a long time, his optimism came across as overconfidence, which wasn’t in keeping with his sensitive soul.

Question: “To the world we dream about, and the one we live in now,” and “If no one takes too much, there will always be enough.” These lyrics mean something different today than they did when Hadestown first opened on Broadway. Can you recall exactly what you were feeling the moment you wrote those specific words, and what they mean for you right now?

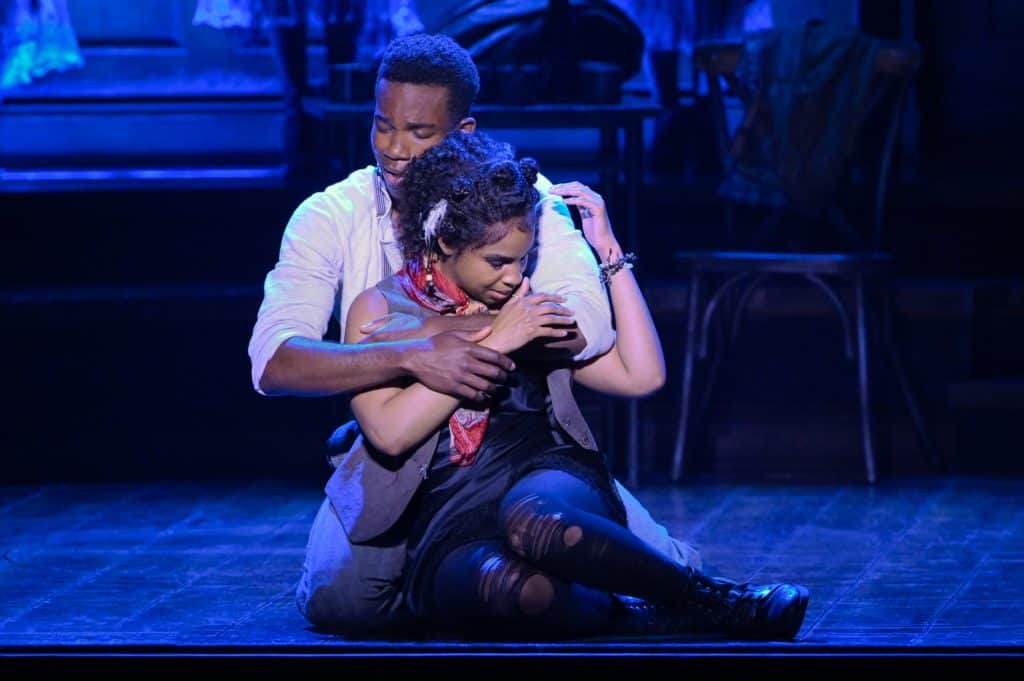

Anaïs Mitchell: To me, those first lines are a reminder that even in hard times, there’s beauty and bravery and cause for celebration. There’s beauty in the struggle for a better a world even if we can’t yet see the result of that struggle. One of the main themes in Hadestown is that there’s value in trying, even if we fail. Orpheus is a hero not because he succeeds—but because he tries!

It meant so much to me to watch our cast perform at Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, and to hear Reeve as Orpheus deliver the lines “And if no one takes too much, there will always be enough.” Something about hearing those lines out loud in a mainstream setting really moved me. Because we live in a culture that takes a lot—we take more from nature than she can sustainably provide. The excesses of a few mean that many go without.

Question: Let’s talk about “Why We Build the Wall.” You wrote that song well before this new political climate, yet the song has completely taken on a new voice. Can you take me through your journey of creating that song? What was your vision for it?

Anaïs Mitchell: I wrote that song in 2006, and it’s one of the few songs that I wrote very quickly, all in one sitting, almost before I understood what it meant. But I do remember what I was thinking about at the time, and that was this: I was imagining a climate in crisis, a world in which many places had become uninhabitable and there were large populations of migrants knocking at the gates of the places of relative wealth and security. And the thought that popped into my head was, “when that happens, who among us is not going to want to be behind some kind of wall?” Leaders (like Hades in Hadestown) have found it effective to use the language of the wall because it speaks loudly to a scared citizenry. The next thought that crossed my mind was the way walling others out has the equal and unintended effect of walling ourselves in.

Question: The presentation of “Why We Build the Wall” is the only number with no added frills—light choreography, somber lighting—it feels more like a conversation with the audience. Rachel, can you tell me what your vision was for the staging of that song?

Rachel Chavkin: The vision for the song was to be as simple and indisputable in its clarity and its politics of fear as the song itself is. And Anaïs is probably the slowest and most specific writer I’ve ever worked with because she’s such a poet, and so she gets angry when songwriters describe, “Oh, I just sat down with my guitar and the song came out.” But she does admit the fact that “Why We Build the Wall” as the song came to her almost cosmically in its full form. As if it had always existed in the atmosphere and she just heard it. The vision was to capture that—a fascist regime in some ways indisputable because it’s so forceful and so clear. We just wanted to make sure the staging, including the lighting design was as simple as the song.

Question: We’re currently dealing with a terrifying pandemic. While many are hopeful, no one knows how this will end or what theater will be like when it reopens. What do you think the show will mean for the post COVID-19 audience?

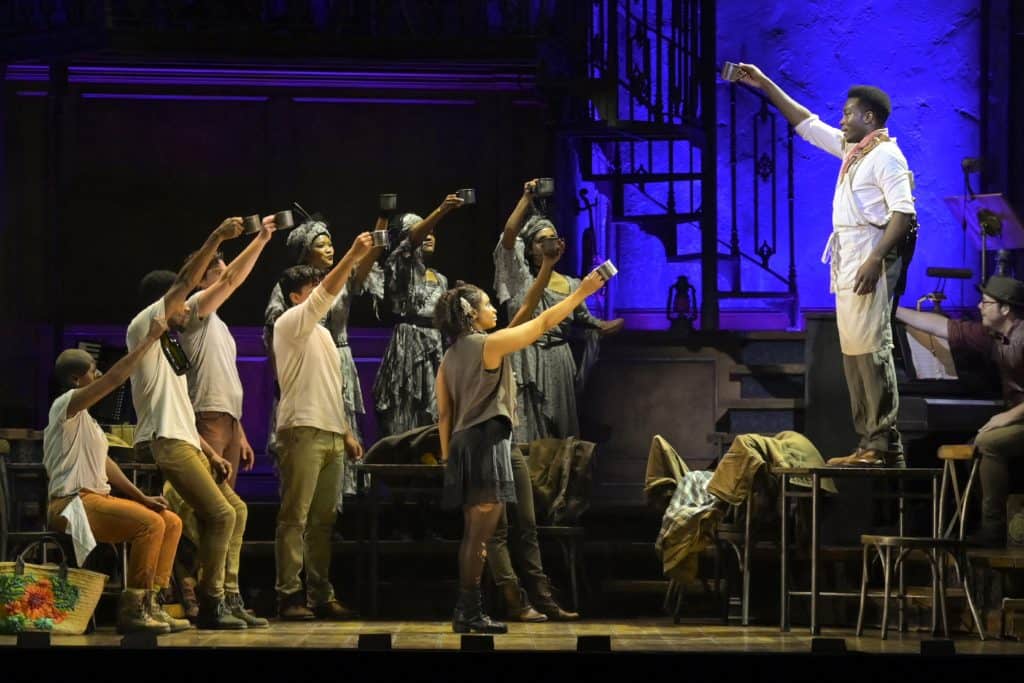

Rachel Chavkin: For me, Hadestown has always been about community. I talked about it in my TONY speech, of how power tries to make us feel alone. But that if we can stand, if we can remember that our lover or our friend may be right behind us. We’re all walking side by side. And I don’t think you need to literally—as in the case of Orpheus and Eurydice—be holding someone’s hand in order to feel fellowship. I think that will remain true and be of comfort in these horrible times.

Anaïs Mitchell: Most simply, I hope audiences will feel healed by the music (at the risk of sounding like a hippie!) I also think the message of Hadestown is one that really speaks to this present moment—it’s a story about hard times, and how people respond to those hard times, sometimes with fear, sometimes with love. And it’s about the necessity of continuing to try even in the face of what feels, at times, futile. It’s also, in a sense, at its climax, a story about the necessity of believing in each other and in our togetherness, even when we feel alone.